From Phrase to Phrasing

A Classical Perspective

Chapter 3 – Phrase-length and Phrase-rhythm

Before continuing it is important to point out some exceptions where the theory does not apply. In random order:

- - Characteristic dances can have cadence-points that are not on the first beat (e.g. Polonaise), or rhythms that prevent complete repose (e.g. Scottish dances).

- - Recitatives have a form that is completely determined by speech rhythm, therefore they are irregular in respect of cadences, phrases and phrase-rhythm. Vocal forms tend to be less regular anyway because the meaning and grammar of the lyrics can not be interfered with.

- - Fugues and pieces in similar style are constructed by different principles where imitations and the continuous weaving of independent voices overrule the need for regular phrases.

- - Fantasies and other improvised music do not necessarily have bar lines, let alone regular phrases. But they need to be judged carefully: some fantasies are regularly structured although notated without bar lines, and free fantasies often contain perfectly regular melodic and thematic sections for contrast.

Phrase-length

Most authors agree that four bars is by far the most common, useful and agreeable length for a phrase. Counting bars seems easy but there are some issues.

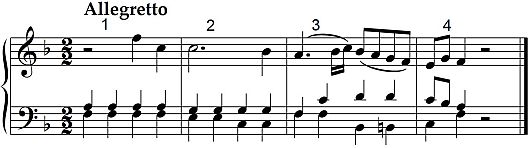

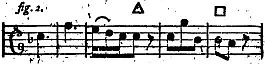

Upbeats can cause confusion. In Figure 21 the upbeat takes more beats than left over in bar 4, but upbeats may be neglected when counting bars.22Heinrich Christoph Koch, Versuch einer Anleitung zur Komposition, 3 vols (Leipzig, 1787), ii, 368.

Figure 21: An upbeat makes the phrase look too long, example by Koch.

In Figure 22 the opposite case: the bass proves the phrase starts before the melody. Since it is therefore not a real upbeat but rather a late entry, the first bar needs to be included in counting.23Heinrich Christoph Koch, Versuch einer Anleitung zur Komposition, 3 vols (Leipzig, 1787), ii, 370.

Figure 22: A late entry instead of an upbeat, example by Koch.

A more surprising issue is the relation between metre and bar count. Theory dictates the cadence-point to fall on the first beat of the last bar of the phrase, counted in simple metre. This is a metre with either 2 or 3 for numerator. A 4/4 is therefore really two 2/4 measures notated in one bar, making Fig. 23 four bars long(!), as indicated by Koch. The proof is in the fact that the cadence-point is then on the first beat of the fourth (virtual) bar.

Figure 23: Cadence-point halfway the bar, example by Koch (vol.II, 372)

According to John Wall Callcott (1766-1821) ‘the Caesure [cadence-point], in ancient Music, most frequently occurs in the middle of the compound Maesure, and thus appears to a modern view irregular and incorrect’–this was written in 1806.24Callcott, A Musical Grammar, in Four Parts, First American edition, from the last London edition (Boston, 1810), para. 509. This old-fashioned way of notating we often find with Haydn who frequently has the cadence-point on the third beat.

Early Classical style tended to move away from the compound 4/4 towards simple 2/4 and 2/2, as stated by Johann Adolf Scheibe (1708-1776).25Johann Adolph Scheibe, Über die musikalischen Composition, im Schwickertschen Verlage (Leipzig, 1773), i, 205. Later in the Classical period 4/4 became more popular again, but with a difference.

Figure 24: The opening bars of Mozart's Violin Concerto K.217 in 'new' 4/4.

Fig. 24 is a ‘new’ type simple 4/4. The proof is the cadence-point at the beginning of bar 4. Koch would have argued that it should rightly have been written in (simple) 2/2 and blames sloppiness and even ignorance of composers and publishers.26Heinrich Christoph Koch, Versuch einer Anleitung zur Komposition, 3 vols (Leipzig, 1787), ii, 295. But a quick survey of scores by Mozart and Beethoven shows the new 4/4 became standard notation. Almost all concertos by Mozart are in simple 4/4 and could just as well have been written in 2/2.

This may seem like a dry theoretical discussion but there are practical consequences. For instance in Mozart’s Quintet for piano and wind, K.452:

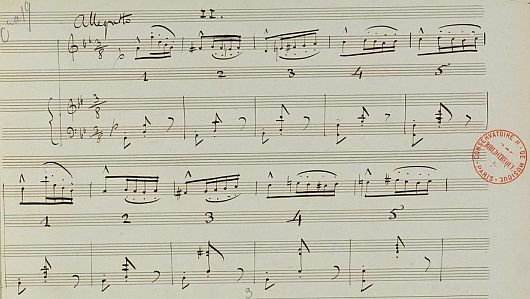

FIgure 25: Mozart, Quintet for piano and wind, K.452, Bärenreiter NMA edition. The metre indication in bar 1 is c.

Recognizing the cadence-point halfway the bar, we realize that there are two phrases of 4 (virtual) bars in 2/4 instead of one 4-bar phrase. Seeing it as two phrases will have you experience two moments of repose, probably leading to a more relaxed tempo, clearer punctuation and maybe a more explicit delivery than when you would try to pace it as one phrase, arching over the break halfway towards the last bar. Dividing it into two phrases does of course not deny that the whole passage belongs together, punctuation also serves to link after all, it only gives a different scope and direction.

It is important to recognize that Fig. 23 and 24 are two different types of Allegro even though the tempo marking and metre are identical. The old type (like K.452) is characterised by the cadence-point halfway through the bar, often with quicker harmony changes and a more active bass line, and is usually played about twice as slow as the new type. It means we can not take metre and tempo at face value without relating it to phrase-length.

We can only speculate why Mozart did not write it in 2/4. Maybe he felt the piece referenced an older style of music that warranted the more traditional notation. Maybe he felt that the many bar lines in 2/4 would visually contradict the broader scope of the movement, making it visually too busy and active. It is interesting that in his 18 piano sonatas Mozart uses a 2/4 only one time in a first movement but 8 times for a ‘finale’ movement. Maybe he wanted to indicate that the first and third (virtual 2/4) bar were the important bars, which could be melodically true but is harmonically less convincing. Though the question can not be answered it definitely has implications for the way each of us phrases and plays the music.

Phrase-rhythm

Having cadences at regular intervals creates a higher level of rhythm, the phrase-rhythm, that is especially important in Classical music. Phrase-rhythm does not have to be constant but it does need to be in balance.

The usual Classical phrase is a 4-bar phrase, or Vierer in German, which I will abbreviate to 4-er. Other lengths are not impossible but they are typically used as a variation rather than the basic unit for a piece. (Antonio Borghese (fl.1777) is the only exception I found, explaining phrases by means of 3-ers.27Borghese, A New and General System of Music, 11.) Even as late as 1885, Saint-Saëns still felt the need to clarify the use of 5-ers in the Scherzo from his Violin Sonata op.75.

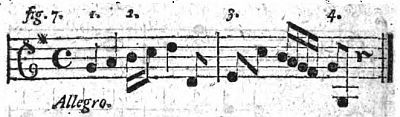

Figure 26: 5-bar phrases indicated by Camille Saint-Saëns, Violin Sonata op.75, mov.2. (Manuscript)

Cadences appearing at regular intervals can become all too predictable (e.g. in Galant style) and Reicha argues strongly in favour of experimenting with different lengths because audiences have become bored by the current predictability of melodies.28Anton Reicha, Traité de haute composition musicale, Czerny edition, 4 vols (Vienna, 1824), ii, 554.

Johann Bernard Logier (1777-1846) illustrates how the ‘spirited (geistvoll) and powerful expression’ created in Mozart’s Serenade K.388 by phrases of 5 + 4 + 3 bars, would be sacrificed if kept in a regular 4 + 4 + 4.29Johann Bernard Logier, System der Musikwissenschaft und der praktischen Composition (Berlin, 1827), 296.

Figure 27: Mozart's original irregular phrases.

Figure 28: Phrases made regular by Logier.

Indeed, it influences expression in a powerful way, but what about Classical balance? When changing phrase-rhythm general advice seems to be:

- - Phrases with even numbered bars are still preferred over odd numbered bars.

- - Use odd numbered bars in pairs to balance them into an even number again.

The phrase-rhythm in the aria ‘Plaire au coeur de ce que j’aime’ by Giovanni Paisiello (1740-1816) is praised by Reicha for being ‘varied in an ingenious way’.30Reicha, Traité de haute composition musicale, ii, 426. According to his analysis the first period is 26 bars (5 + 5, 2 + 2, 2 + 2, 4 + 2 + 2), the second 18 (5 + 5, 2 + 2, 4). A final phrase has been added to close the aria with more character (3 + 3 + 2 + 2). The phrase-rhythm is definitely not regular but still highly symmetrical, every odd number paired with a compagnion (Reicha) to maintain balance.

He opposes this by the aria ‘Ah! Que je fus bien inspirée’ from Dido by Niccolò Piccinni (1728-1800) with a first period of 29 bars (3 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 7 + 5) and a second of 40 bars (6 + 6 + 3 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 + 5). Reicha claims the, otherwise well-composed aria, has a shaky, undecided melody that is hard to remember, and he blames lack of symmetry in phrase-rhythm for making the individual phrases appear unconnected.31Reicha, Traité de haute composition musicale, ii, 465.

Phrase-rhythm is not just a theoretical concept. Especially Haydn is a master of irregular phrases and the phrase-rhythm adds spice and originality, but also more than that: the composer apparently needed to deviate from the norm to express something that could not be expressed within it. In order to bring that across in our playing we need to recognize the three techniques to vary the length of a phrase:

- - Invent a melody that sounds completely logical and complete at this different length (Koch calls this a ‘narrow’ phrase, eng).

- - Add more material to a standard 4-er (an ‘extended’ phrase, erweitert).

- - Combine 2 phrases into a longer one (a ‘compounded’ phrase, zusammengesetzt).

Extended phrases

Repetition

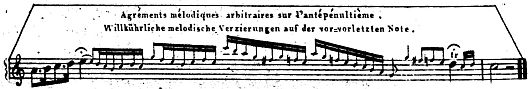

The most common way to extend a phrase is by repeating a part of it. Looking at Paisiello’s aria from Reicha’s analysis, we see the first 5-er was created by repeating two halve bars from the original 4-er:

Figure 29: Paisiello's phrase of 4 bars extended into 5 by repetition.

There are many possibilities: you can repeat 1 or 2 bars literally, or embellish the repeat, or even repeat them at another step of the key. Two examples by Koch:

Figure 30: (A) Extended by 2-bar repeat on different step of the scale, (B) extended by repeating 1 bar embellished. Examples by Koch (II, 431 en III, 161)

Whereas the Paisiello example is an obvious repeat, the Koch examples are less easy to recognize. Sometimes it is hardly possible to decide whether a 4-er was extended or simply conceived as a narrow 5-er, like in Schubert's C minor Impromptu D.899,1. Is bar 3 a repetition? It can be left out after all.

Figure 31: Schubert Impromptu D.899,1 - a narrow 5-er or an extended 4-er?

Whatever you call it, this 5-er (which follows eleven regular 4-ers) is one of the most beautiful changes in phrase-rhythm in the literature.

Importantly, repeating part of a phrase is more than a mechanical process. Koch states the repeated motif must be ‘worthy’ of repeating: it needs to represent the expression of the phrase in a high degree, or highlight a new aspect of it.32Heinrich Christoph Koch, Versuch einer Anleitung zur Komposition, 3 vols (Leipzig, 1793), iii, 155. The Paisiello is an excellent example: the repeated passage has the text de ce que j’aime (‘of the one I love’); a worthy subject to dwell upon. Musically a repetition can be highlighted by changing dynamics, adding embellishments, creating a new twist in the accompanying voices (harmony, texture), etc. Though Koch is writing for aspiring composers it is also inspiring advice for performers, really giving us a chance to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

Repetition does not fundamentally change the proportions of a phrase because the repetition can be omitted. With added repetition, Reicha claims, a phrase usually still sounds even numbered instead of the odd bar count it looks. The inserted bar ‘has something appealing because it adds originality and attraction’.33Anton Reicha, Traité de haute composition musicale, Czerny edition, 4 vols (Vienna, 1824), ii, 457.

Expansion

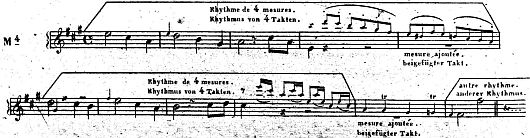

By expansion one bar gets stretched into two like Koch illustrates:

|

|

Figure 32: (left) A narrow phrase, which is expanded into a 5-er (right). Example by Koch (III,171).

Expansions lend more weight to a phrase. Expansions at the beginning of phrases are typically found at the grand finale of a bigger composition, particularly oratorios. Expansions at the end of a phrase usually broaden the cadence to finish a section with more grandeur, often used in solo concertos. Reicha considers this retard de la cadence a pleasant way to break symmetry. In chamber music it is often notated with fermatas as in Fig. 33 (a), in concertos it is usually written out like (b).34Anton Reicha, Traité de haute composition musicale, Czerny edition, 4 vols (Vienna, 1824), ii, 399.

Figure 33: Retard de la cadence, examples by Reicha.

The difference in notation demonstrates that in essence the phrase-rhythm has not been disrupted even though the bar count has. If the cadence is embellished we get a proper cadenza; this type of free cadenza again does not change the bar count.

Figure 34: Cadenza by Reicha over the previous example.

It is important to realize that the cadenza is not a ‘stop’, the phrase must still finish and Reicha warns that a cadenza should never be so long as to make the audience forget the resolution of the cadence ‘that it rightfully so eagerly awaits.’

Other techniques

Repetition and expansion add melodic material ‘from the inside’. Koch lists several other techniques that add on (usually) less substantial material. Their less distinctive features make it unlikely to upset the balance in phrase-rhythm.

- - inserting/repeating a characteristic rhythmic pattern.

- - using a progression, which is a sequence of the same material on different steps of the scale.

- - using a passage which is basically adding unsubstantial passage-work. In this way you can easily create very long phrases.

- - with an interpolation you can insert non-related phrase-parts into the phrase. They must however add meaning to the existing phrase.

- - with an appendix (Koch: Anhang, Reicha: addition) you add material at the end of the phrase. An appendix can give more decisiveness to a cadence or, the opposite, move towards a cadence on a different chord. Often the appendix in its turn gets an appendix, which leads to another appendix, etc.; this can extend the material substantially. Or the appendix can be just an added bar in another instrument. as in this example by Reicha:

Figure 35: Appendix by added bars in orchestra, example by Reicha.

- Reicha: ‘If used well, the addition has such an appealing effect: it is like a hesitant lingering, almost taking breath to better comprehend what follows. Without the addition the melody in the example would be worn out and less appealing.’35Reicha, Traité de haute composition musicale, ii, 456.

- - A prefix usually acts like in introductory statement and is therefore not really a part of the melody and unlikely to upset the balance in phrase-rhythm. Importantly, Koch acknowledges that some extensions cannot be described by a certain technique or reduced to a shorter original; they are simply created by the genius of the composer.36Heinrich Christoph Koch, Versuch einer Anleitung zur Komposition, 3 vols (Leipzig, 1793), iii, 205.

The Mozart game

Figure 36: Illustration from talkclassical.com

Despite the previous remark, Koch treats extensions under the heading ‘About the art of connecting a melody according to mechanical rules’. This gave me the idea for an ‘app’ to play around with extensions. It is based on the first 2 phrases of Mozart's Musikalisches Würfelspiel (musical dice game) K.294d where a different minuet is ‘composed’ depending on how the dice roll.

I have taken the game one step further by having the dice add extensions according to Koch's methodology. The first aim was to test how these extensions can work within phrases. But it also illustrates Koch’s remarks about different genres requiring different kinds and amounts of extensions. Consequently by having the app add extensions, the minuet is taken away from its dance foundation and turned into something more akin to the opening of a sonatina. Besides clicking ‘auto extension’ it is also possible to experiment manually by clicking the check boxes. Of course the musical outcome of this mechanical experiment will necessarily be contrived but sometimes interesting examples appear!

EXTRA DICE 1

|

EXTRA DICE 2

|

Compounded phrases

Where extensions vary the phrase-rhythm by changing the length of a single phrase, compounded phrases create a different phrase-length by connecting 2 (or more) phrases in such a way they seem to be only one. Basically there are two ways: bar suppression and denying completion.

Bar suppression

When the chord on which the cadence lands is identical to the opening chord of the following phrase you can often leave out one bar. The German word Takterstickung (bar suffocation), and the term ‘interwoven’,37Callcott, A Musical Grammar, in Four Parts, First American edition, from the last London edition (Boston, 1810), para. 567. are more graphic descriptions of the technique. Below two examples from Mozart’s violin concertos, each with a completely different result.

The orchestral introduction of the G major concerto, K.216 shows two phrases clearly set apart:

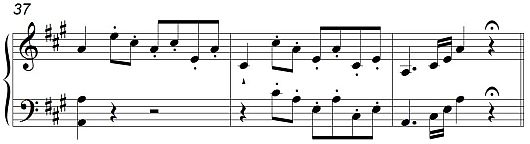

Figure 37: Mozart Violin Concerto no 3 in G, K.216, bar 17.

Similarly we would expect at bar 72:

Figure 38: Mozart Violin Concerto 3 in G, K.216, bar 72 without bar suppression (my reconstruction).

but instead the fourth bar is suppressed, creating a smooth connection.

FIgure 39: Mozart Violin Concerto no 3 in G, K.216, bar 72 with bar suppression (original).

This is made possible by the identical chord and leaving out the upbeats. Riepel advises to omit upbeats in bar suppression anyway.38Joseph Riepel, Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst: De Rhythmopoeïa oder von der Tactordnung, 7 vols (1752), i, 58. According to theory, you are supposed to count the bar where the suppression happens twice, so what could look like a 7-er still counts as eight (4 + 4), therefore balance is maintained and phrase-rhythm does not feel disturbed.39Heinrich Christoph Koch, Versuch einer Anleitung zur Komposition, 3 vols (Leipzig, 1787), ii, 454.

In the A major concerto, K.219 the orchestral introduction ends with the following appendix after which the solo violin enters:

Figure 40: Mozart Violin Concerto no 5 in A, K.219, bar 37 appendix.

Mozart could have used a similar construction before the violin entrance in the development section:

Figure 41: Mozart Violin Concerto no 5 in A, K.219, bar 116 without bar suppression (my reconstruction).

instead he suppresses the bar before the entrance,

Figure 42: Mozart Violin Concerto no 5 in A, K.219, bar 116 with bar suppression (original).

creating almost a shock effect—no smooth transition but rather a plunging into. In this case the chords are different, taking the conventional bar suppression to a different level, but the technique is essentially the same.

Denying completion

Another way to compound phrases is to deny completion by taking away the feeling of repose of the cadence, hence forcing another phrase to be added on. The most familiar and powerful way is by harmony with (the surprisingly apt named) deceptive and interrupted cadences.

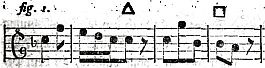

But it can also be done by melodic means. In Fig. 43 the top stave has two regular phrases of 4 bars, the first divided into two phrase-parts. On the bottom stave the melodic cadence in bar 4 has been weakened: loss of completion now turns it into an 8-bar phrase with three phrase-parts.

Figure 43: Top stave has two phrases of 4 bars, bottom stave one phrase of 8 bars by denying completion. Example by Koch, II, 459.