From Phrase to Phrasing

A Classical Perspective

Chapter 7 – The Performer as Composer

Apart from influencing phrasing, phrase theory can also be helpful in situations where the performer gets close to being a composer himself. Some real-life examples.

Figured bass

Figured bass practise was still very much alive in Classical repertoire (specially in songs) and phrase theory can be helpful. For instance, top notes are influential in determining the strength of a cadence and hence punctuation; this is particularly important when playing with lower instruments and voices where the right hand accompaniment is forced to play the highest note of the chord, on top of the melody. More in general, awareness of punctuation can be a guide towards filling in ‘gaps’ in the melody, and awareness of the development in a phrase can be supported by pacing the activity of the right hand.

Ornamentation

Koch and Reicha recommend never to have two identical cadences following each other, to prevent uniformity and lack of clarity in punctuation. If forced to repeat the same harmonic cadence it must be at least melodically and/or rhythmically different, as demonstrated by Koch in Fig. 92.82Heinrich Christoph Koch, Versuch einer Anleitung zur Komposition, 3 vols (Leipzig, 1793), iii, 67.

Figure 92: Two different phrase endings on identical harmony, example by Koch (abridged).

The point I want to make is that, when embellishing, we should take care not to accidentally make endings too similar, as I did on purpose in Fig. 93.

Figure 93: Koch's previous example, badly ornamented by me, creating too similar phrase endings.

Also Reicha warns that in embellishing, phrase-rhythm and cadences should never be changed.83Anton Reicha, Traité de haute composition musicale, Czerny edition, 4 vols (Vienna, 1824), ii, 497. In his examples of lavishly decorated arias (copied down from famous singers) the end of a phrase is almost never changed. Occasionally a conduit (lead in) is added to the next phrase but it always leaves a pause for punctuation.

Figure 94: Original version (top), and ornamented with a lead in (bottom), example by Reicha.

The only place where a phrase ending gets significantly embellished and changed is at a point d’orgue (fermata) but by then we have crossed into the realm of the cadenza.

Case study 4: Creating the introduction to a song

Many Classical songs have no piano introduction, forcing the singer to pick the first note out of the air. Since this was an age where performers routinely improvised preludes to introduce a composition (Hummel84Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Ausführliche theoretisch-practisch Anweisung zum Piano-Forte-Spiel, second edition (Vienna, 1827), 465.), it seems highly unlikely they would allow for such an abrupt start of a song. In church services this is still a regular practice.

Nowadays the postlude is often used as a prelude in order to stay as close as possible to the original composition. That doesn’t always work well. In the early Schubert song ‘An den Mond’, D.259 (1815) it would create:

Figure 95: Schubert's An den Mond, D.259, using the postlude as introduction.

Though I’ve heard it performed like this, some things don’t sit well. (1) The first chord is dissonant, which is not impossible but usually reserved for a special effect. (2) The dense harmonic rhythm suggests an ending rather than an opening, melodically and harmonically it comes to a close. Also it would be unlikely for a composer to give away the most special chords at the beginning of a piece. (3) The construction of the phrase with its one bar phrase-members and tricolon suggests fragmentation (and therefore a continuation) though there is nothing yet ‘to fragment’ or to continue; if we look at the song itself it shows the postlude is indeed the continuation of a phrase (bar 9-12) rather than an appendix.

The usual written-out preludes in Classical songs are either original inventions, something musically neutral, or a combination of the opening and final measures of the song. Original inventions fall outside the scope of this paper but a neutral opening could be something like:

|

|

Figure 96: Schubert's An den Mond, two possible neutral introductions.

Both are possible but quite boring. The second example needs two bars to keep an even bar count, in the first example the chord doesn’t really participate in the song yet and therefore one bar can be enough.

Combining the opening and end measures of the song would produce something like this:

Figure 97: Schubert's An den Mond, combining opening and final bars - version 1.

Bar 3-4 are melodically rather wild compared to 1-2. This often happens: by the nature of things opening measures are usually simple whereas the end measures conclude a certain development. I would therefore reduce the energy of the second part by limiting the compass of the melody line and simplifying the rhythm:

Figure 98: Schubert's An den Mond, combining opening and final bars - version 2.

Case study 5: Writing cadenzas

To cover this topic extensively would fall outside the scope of this paper. My aim here is to to demonstrate the usefulness of phrase theory by means of a simple template I made. It is definitely not a historical model or a manual to create cadenzas, though it can serve as a foundation to elaborate on.

Rather than trying to string melodic ideas from a concerto together, I would suggest to start with a basic lay-out of phrases: an introductory phrase, a melodic phrase and a concluding phrase. Though historically you are not obliged to use themes from the concerto, it is often easier than inventing something new. But I would advise using the material in a very free way, just to trigger ideas and stay in style. Being literal normally does not work because the original material is made to fit the development of the piece, whereas the cadenza has its own development.

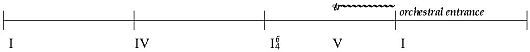

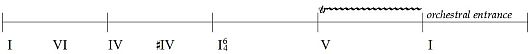

It makes sense to start at the end because it is fixed: always I64-V-I. A basic phrase would suffice, four bars with some harmonic acceleration towards the end:

Figure 99: Outline for a basic final phrase of a cadenza.

We can add some chords in between to increase harmonic rhythm, thereby making clear we reach the conclusion of several phrases. Expanding the cadence would also be appropriate:

Figure 100: Outline for a more elaborate final phrase of a cadenza.

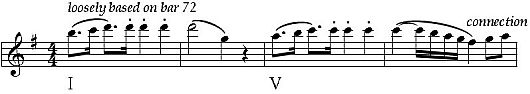

You would usually fill this with scales and passage-work for a virtuoso finish. To illustrate I will use Mozart’s Flute Concerto no 1 in G, K.313 as an example:

Figure 101: Final phrase filled in.

We can easily lengthen the cadenza by putting a melodic phrase before it, pinching some melodic intervals from a theme and turning them into a bicolon. Harmonically I-V-V-I or I-V is enough, with a bridge to the (already composed) next phrase.

Figure 102: Melodic phrase filled in.

Now we still need an introductory phrase. Starting with an upbeat is always a good way to get going; using scales and chords on alternating I and V would be enough to ‘start exploring’. Finishing on the dominant can properly introduce our melodic phrase:

Figure 103: Introductory phrase filled in.

Of course this needs to be polished, and more phrases can be added or extended, but at least a proper framework is in place that will yield results quicker than stringing one’s favourite melodic bits together and hope for the best.